“A horse so prancing is a thing of beauty, a wonder and a marvel;

riveting the gaze of all who see him, young alike and graybeards.”

400 BC

Dressage was “born” in ancient Greece. Xenophon, a friend of Socrates, historian and soldier, is regarded as its forefather. While creating training methods to make his cavalry horses more responsive and maneuverable in battle, Xenophon developed everything from simple equitation to more advanced schooling techniques. He valued military precision, but also trust, grandeur, suppleness and a quiet seat. His treatises “On Horsemanship” & “The Cavalry General” are the earliest surviving works on the fundamentals of equestrianism.

Source: “Xenophon, Forefather of Dressage,” by Abby Gibbon, 2011

Photo: Xenophon and the Ten Thousand Hail the Sea, by John Steeple Davis , 1900

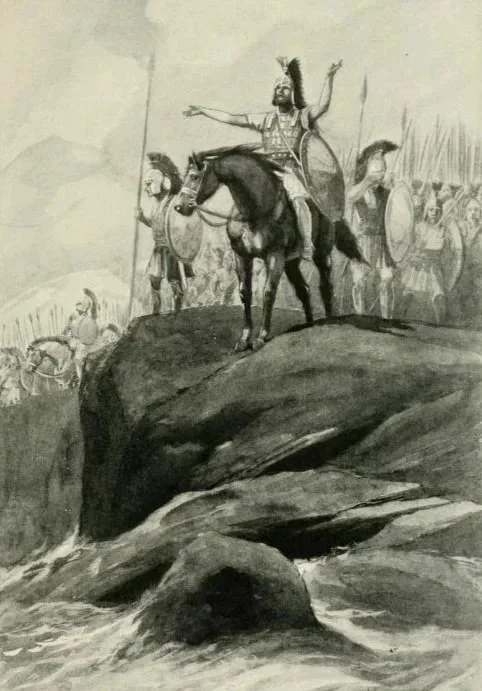

15th c.

Dressage grew out of ancient military riding schools and became more sophisticated and graceful during the Renaissance. Several well-known academies were established for equestrians to perfect classical riding and to perform exhibitions for the noble classes. They focused on the development of advanced movements, with the Spanish Riding School in Vienna becoming the most famous. This is likely because Spanish horse breeds - especially the Lipizzaner - are well suited to dressage and the Hapsburg court enjoyed using them for this purpose. Renowned for their strength, agility and trainability, the “Dancing White Horses” were brought to Austria from the Iberian Peninisula to train young aristrocrats in the art of dressage.

Source: “Equestrian Dressage: History, Competition & Rules,” by Caroline Cochran, 2024

Photo: Festivities at the Spanish Riding School during the Congress of Vienna, 1815

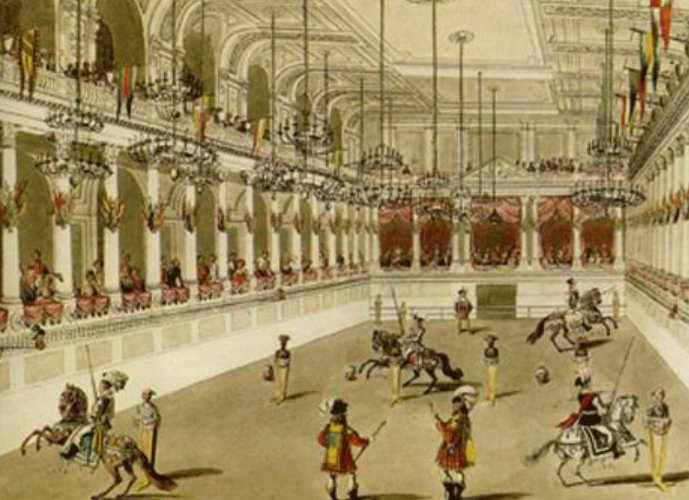

18th-19th c.

Dressage arena markers are a historical mystery. The letters A-K-V-E-S-H-C-M-R-B-P-F that are used with a standard 60m x 20m dressage court are essential for competitions, but their origin is disputed. One of the more plausible theories is that they were locations within the Imperial Prussian Court's cavalry barracks. Because almost 300 horses lived at the Royal Manstall, a system was needed for assigning mounts to riders for daily exercises or parades. It is possible that markings on the walls of the yard corresponded with the spot where a groom would hold a horse for a specific person. “K” may have indicated the Kaiser, for example. Another strong theory attributes the system to the German Cavalry Manual of 1882, which shows a diagram of a 40m x 20m arena (the modern small court) with A, B, C & D marked in each corner, and E & F positioned in the middle of each long side. The topic is fascinating, as are the mnemonics that dressage enthusiasts use to help them remember the sequence of letters.

Photo: Diagram of riding arena in German Cavalry Manual, 1882

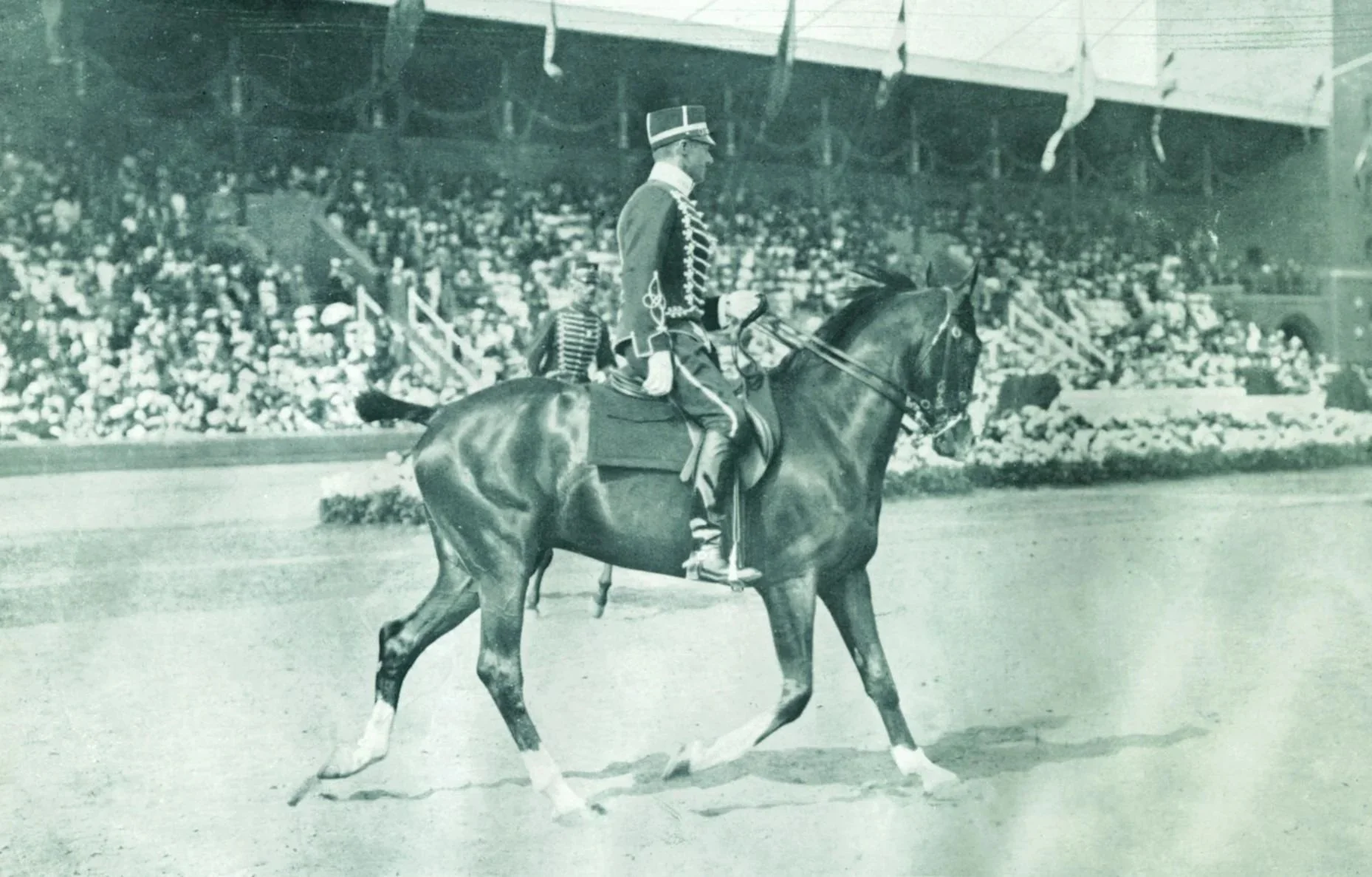

1912

Dressage debuted in the Olympic Games in Stockholm, thanks to the many members of the nobility on the International Olympic Committee. Only “gentlemen” riders were invited to compete, meaning that women and non-commissioned officers were excluded. The test was held in a 40m x 20m arena and focused on military obedience. It included 5 jumps and a barrel that had to be cleared while it rolled towards the horse. Bonus points were given if the rider was able to jump the moving target with his reins in one hand. Unlike today, only an individual event was contested, in which there were 21 riders from 8 countries. Carl, Count Bonde of Sweden, won the gold medal with his mount, Emperor.

Source: “Equestrian Dressage at the 1912 Summer Olympics,” Olympedia, 2006

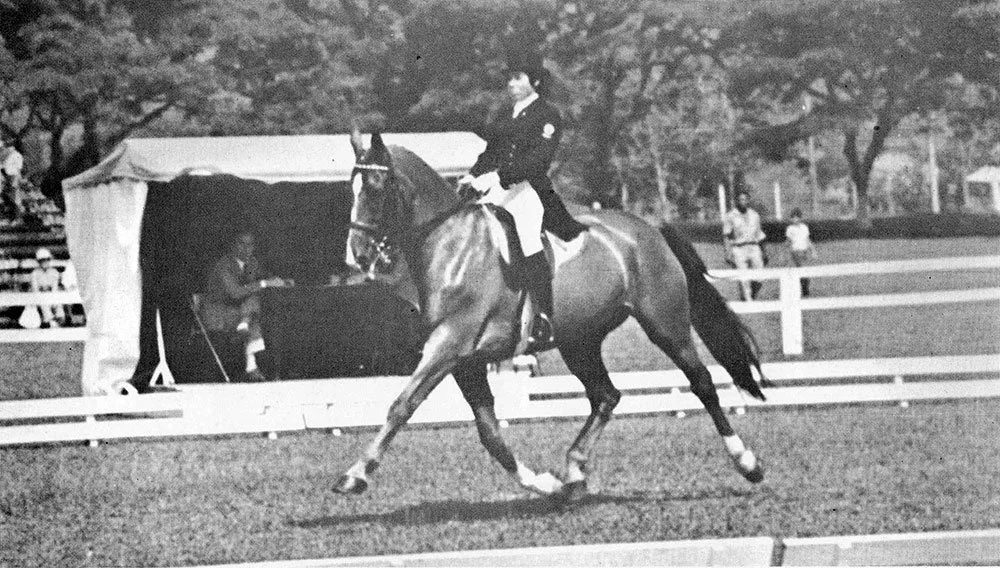

1920-1948

Dressage gradually evolved glolbally. At the Antwerp Olympics, collected walk, trot & canter were included, as well as extended trot, counter canter, and tempi changes. The Amsterdam Games added a dressage team event. In Los Angeles, piaffe and passage were finally added to the tests, as were the letters around the court. Canter pirouettes and five loop serpentines were first shown in Berlin. By 1936, Olympic dressage tests consisted of 22 movements to be completed in 17 minutes. Unfortunately, due to World War II and a lack of preparation time, piaffe and passage were removed from the London games, but renvers and half-passes were tacked on. Male cavalry officers from Sweden, Germany, and France dominated the podium.

Source: “A History of Equestrian at the Olympic Games,” Horse Quarterly Magazine , 2021

Photo: The Equestrian Stadium at the Riviera Country Club, Xth Olympiad, 1932

1952

Dressage was opened up to male and female civilians for the first time at the Olympic Games in Helsinki. Since then, it has been one of very few high performance sports where both genders compete against each other on equal terms. Lis Hartel of Denmark quickly became the first woman to win an Olympic medal in equestrian sport (women weren’t permitted to jump until 1956 and eventing was allowed in 1964). Hartel took silver in the individual dressage test in Helsinki in 1952, followed by another in Stockholm in 1956. Not only did she defeat all but one male competitor twice, but she did so with limited mobility. At 23 years of age, while pregnant, Hartel had been struck with polio and was partially paralyzed. Her achievement against able-bodied athletes was remarkable and a testament to the harmonius relationship she built with her partner, Jubiliee.

Source: “Women in History: No Obstacle Was Too Great for Lis Hartel,” by Chris Stafford, 2024

Photo: André Jousseaume, Henri Saint Cyr & Lis Hartel in Helsinki, 1952

1971

Dressage enthusiasts celebrated Canadians Christilot Hanson (Boylen), Cynthia Neale (Ishoy), Lorraine Stubbs and Zoltan Sztehlo’s performances at the Pan-American Games in Cali. Together, they won the team event, while Hanson (Boylen) also won a gold medal in the individual test. She would repeat in 1975 and 1987, and top the team podium again in Indianapolis, alongside Diana Billes, Eva Maria Pracht and Martina Pracht. At the 1991 games in Havana, Lorraine Stubbs, Ashley Munro, Gina Smith and Leslie Reid struck gold once more, with Stubbs and Munro finishing first and second in the individual test. Reid was the individual winner again in 2003, with another Pan-American gold eluding Team Canada until 2019.

Source: “Equestrian Sports,” by Barbara Schrodt & Lorraine Snyder, 2012

1988

Dressage hit its historical peak for elite Canadian athletes. At the Seoul Olympics, Gina Smith, Cynthia Ishoy, Ashley Nicholl (Holzer), and Eva Maria Pracht won a bronze medal. At 51 years of age, Pracht was the oldest Canadian female medallist, a record held until 2012. It was also in Seoul that Ishoy posted Canada’s best-ever individual result, just missing the podium in fourth place. A Canadian has yet to win another Olympic medal in the sport.

Source: “Canada’s Olympic Dressage History (Pre-Paris 2024),” Olympics.ca, 2024

1996

Dressage became more popular at the 1996 Atlanta Olympics with the introduction of the freestyle, known in German as kür. Similar to a free skate in figure skating, it allows riders to choreograph a routine set to music of their choice. Perhaps because of the extra artistic element, or maybe because the human athletes can play to the strengths of their mounts and incorporate more difficulty into their tests, Dutch and British individuals have joined Germans on the Olympic podium ever since. Regardless, the overall increase in viewership, sponsorship, broadcasting and “influencing” due to the entertainment value of kür has broadened the sport’s reach.

Source: “The Evolution of the Musical Freestyle,” by Axel Steiner, 2015

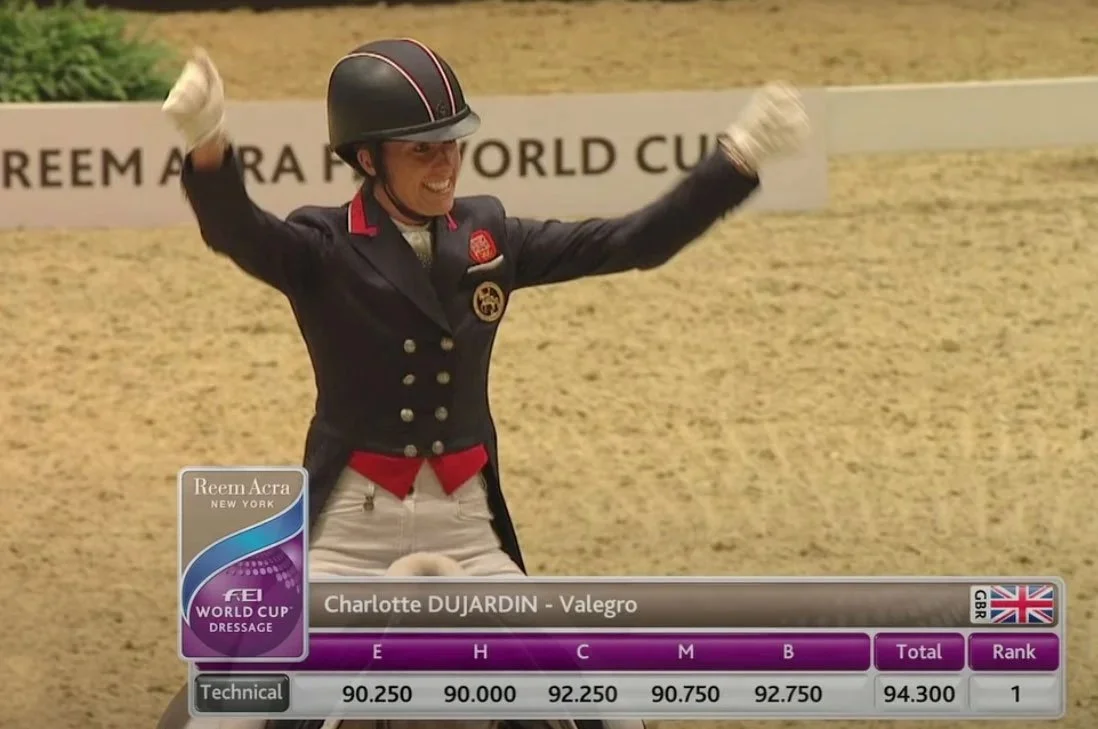

2012

Dressage riders in Canada were the first in the world to adopt a rule requiring helmets at the national level. After American Olympians Courtney King-Dye and Günter Seidel were seriously injured in 2010, the traditional top hat came under scrutiny. The United States quickly followed Canada’s lead, mandating the wearing of safety helmets at all of its USEF events. The FEI received two formal petitions against the rule and was under pressure from European lobbyists, but it voted to ban top hats in 2019, and ultimately did so in 2021.

2014

Dressage tests hardly ever receive percentages that most people associate with an “A” as scores over 80% are rare. The highest mark in history - and a Guiness World Record - is 94.300%, awarded to British equestrian Charlotte Dujardin and Valegro in the kür at the 2014 FEI World Cup in London. The pair also holds the record for the Grand Prix (87.460%) and Grand Prix Special (88.022%). Solid performances generally earn 60%-70% from judges, no matter the level, venue or competition. Consistent scores over 65% indicate that a horse and rider may be ready to advance.

Source: “Equestrian Dressage: History, Competition & Rules,” by Caroline Cochran, 2024

2025

Dressage is supposed to look effortless, much like ballet. Even though both horse and rider are often working very hard, movements should be fluid and harmonious. The signals given by an equestrian to his/her/their partner are meant to be almost invisible to the observer and more of a silent conversation between two athletes. The modern objective is to demonstrate a horse’s natural three paces while performing a series of prearranged movements, and to do so without tension or any semblance of force. Rule changes by governing bodies reflect an increased focus on horse welfare and social license to operate, a term coined by Canadian executive Jim Cooney in 1997. It is our collective responsibility to respect and care for these amazing creatures and to ensure that our beautiful sport can be enjoyed for another two thousand years.

Source: “SLO in Equestrian Sport: What Does the Future Hold?,” by Li Robbins, 2025